– John F. Kennedy

Above all the Cold War was fought at the cultural front. To think of culture, especially the fine arts, as a front or even as a weapon that transports and exports ideological ideas and is used to reinforce propaganda, certainly wasn’t invented during the Cold War, but assumed proportions that were without equal.

The cultural war flared up in postwar Germany and Austria. The goal was not only to prevent the resurgence of Nazism and Fascism, but especially to bind Germany to the West or to the East. Both, the Soviet Union and the United States were highly aware of the symbiosis between political and cultural connections. So it isn’t surprising that the first years of the Cold War, from 1950-55, were mainly characterized by the linkage of aesthetic rejection and enemy stereotypes.[1] Further, lots of money was spent, institutions founded and programs established to spread or control culture and art. To name just two different approaches: In the East the Artist Association of the GDR (Verband Bildender Künstler der DDR) was founded in 1950, which paved the way for state commissioned art[2], and in the West the Emergency Fund for International Affairs was established by President Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1954[3] to demonstrate the “superiority of the products and cultural values of [America’s] system of free enterprise”[4].

The famous discussion of what is considered art became attached to a political component. Abstract art was a synonym for free art, the art of the West, THE postwar aesthetic. That this was also due to the subversive activity of the CIA is often forgotten.[5]

Socialist Realism became the art of the Socialist workers, the Communists – or as seen in the West, the art of totalitarian states and therefore no art at all. Artists who did not meet the party line were oppressed or even persecuted.[6]

The Cold War era was characterized by fear that dwindled into paranoia. The constant anxiety of infiltration by the enemy, gave cultural exchange a tension and meaning that is hard to reconstruct today. A picture, an exhibition, a theatrical play or musical suddenly could represent a regime or be misused by the opponent for propaganda needs. Therefore, not only the opponent’s art was feared to undermine society, but it was also the artist and his art production that was carefully chosen, before being shown abroad.

When Everyman Opera Inc. toured Western Europe from 1952-56, performing Porgy and Bess, they were at first generously supported by the US government ($707,000 + transportation).[7] The support ended, however, when they were invited to perform in the Soviet Union, because the American government feared they would have to provide visas to Soviet artists in return.[8] Further it was not foreseen that the performance would be a success. The socio-critical plot of the opera, addressing slavery in the United States, one of the most sensitive topics in American history, could have been easily exploited for Soviet propaganda.[9] None of this happened. The critics were mostly positive, and the first American performance in Russia since the founding of the Soviet Union, must be considered a huge success.[10]

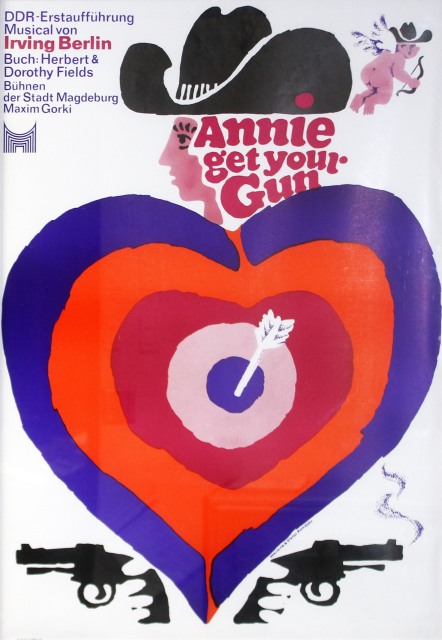

An example of how things could have developed differently, would be the reception to Annie Get Your Gun in the German Democratic Republic’s (GDR) daily newspaper Neues Deutschland in 1950. The heading of the article read “Warmongering with sex-appeal, ” and described Betty Hutton as a “grinning beast”.[11]

But the paranoia and the agitation against everything not meeting the party line in the GDR, didn’t stop at American productions. It also affected the GDR’s own poetic figurehead Bertolt Brecht. Although he was a professed communist and voluntarily moved to the Soviet Occupation Zone when he returned from exile in the U.S. after the war, he was censored and criticized by the authority. They deeply distrusted him and his self elaborated “epical theater” (later “dialectical theater”) was rejected. [12] His “Threepenny Opera” was called an apotheosis, with a lack of class-conscious statements and exemplary characters.[13] The turning point came in 1955 when Brecht was awarded the Stalin Peace Prize in Moscow. Only then did the GDR fully accept him as a state-poet.[14] He died one year later at the age of 58. True to the motto “only a dead poet is a good poet,” the GDR government exploited Brecht and his work for their purposes. Brecht had never allowed himself to fully criticize the GDR, although he was more than disappointed by the lacking revolutionary vigor of the Socialist Unity Party (SED) and did not agree with the official party line.[15]

Nevertheless, I think the case of Brecht is somehow sad. His personal fate is unique, yet also exemplary and descriptive for the time. A lot of artists who truly believed in the communist ideology shared Brecht’s fate, which is only proof to how little the existing Socialist states had in common with the ideas they claimed to stand for. This should be kept in mind and is sometimes forgotten in the nostalgic reminiscences of today known in German as: “Ostalgie.”

The success of Porgy and Bess, however, shows that culture and fine arts can be understood and appreciated everywhere. Even in a time when fine arts were used as weapons and propaganda there also was understanding and interest. Culture is something humankind has in common not something that divides us.

Felicia Grudzien